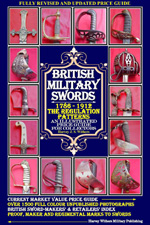

This article is taken from my book – British Military Swords 1786-1912. An Illustrated Price Guide for Collectors. To order a copy please go HERE.

A Yeomanry Cavalry Trooper, c.1890.

Here we find a contemporary account of the history of the British Militia System. Many thousands of Britons joined its ranks and the inevitable demand for swords was very high. The 1827 Pattern Rifle Brigade Officer’s Sword is a familiar weapon for the collector and a great number were produced for both the town and village volunteer. This also excludes large quantities of swords passed on to both cavalry and infantry units by the regular army, when deemed unfit for active service. Although the subject matter of this article is not particularly sword related, it is still an excellent and dispassionate summary of the British volunteer movement, and a great insight into the typically “English“ and benign nature of its development and ethos. The purchase of a volunteer sword can also be the gateway to further research into these sadly neglected regiments who were once inextricably bound up with the social fabric of the British nation.

The British Volunteer System

The Rt. Hon. Earl Brownlow

Formerly Under-Secretary of State For War

from the NORTH AMERICAN REVIEW, MAY 1900

The early years of the century found England in the possession of a large body of volunteers. They were not a part of the permanent military organisation of the country, but were raised in a hurry, and for a special purpose, and were only intended to meet a sudden emergency. At that period, Napoleon I had massed a great army at Boulogne in sight of the British coast; but the British cruisers held the Channel, and day after day and month after month passed, until the naval battle of Trafalgar put an end forever to his ambitious dream of the conquest of England. It was to meet this contingency that the Volunteers of 1803 were raised, and the danger having been averted, they were disbanded and never brought together again.

With the organization and efficiency of this force, this article is in no way concerned, and it is only mentioned here to explain that volunteering for defense of the country is no new idea, but that the volunteers of 1803 have no relation to those of 1858. They served their purpose; they came together to the number of 463,000 men, and when the emergency ceased, they died out and disappeared.

They seem to have incurred at that time a certain amount of “chaff” on account of their somewhat crude idea of military duties, and it is said that one regiment having repeatedly pointed out to Mr. Pitt that they only volunteered to repel invasion, and were on no account to be sent out of the country, he replied that he would promise not to send them away “except in the case of invasion.”

There is, however, one volunteer corps – the Honorable Artillery Company of the City of London – which is quite exceptional. It dates from the time of Henry VII, at which period it wore a picturesque dress, had nothing to do, and “did it very well;” and it consists of artillery, cavalry and infantry. It is not a “company” in the military sense, but has many of the attributes of the City of London companies, and has property and funds of its own.

This ancient corps has its counterpart in the Honorable Artillery Company of Boston in the United States, the members of which some time ago visited London and received a cordial welcome as a link between the Old and the New Worlds.

Until 1858, the Honorable Artillery Company was the only old-established Volunteer Corps. At that time, the country was thirsting for peace and rest. The Crimean War had disclosed a state of military disorganization in the army which had caused misery and disaster to the troops during the war, and it was felt that only the bravery and pluck of the officers and men had saved the country from actual defeat; but when peace with Russia had been obtained, no time was given for reorganization. The Indian Mutiny, following on the heels of the Crimean war, called forth all the resources of the Empire; but, when tranquillity was again restored, the public mind once more turned to the contemplation of army reform.

…soon became known that the would-be assassin had hatched his conspiracy and manufactured his bombs in England; and, in the excitement that ran like wildfire through the French army, a hundred French colonels signed a petition to the Emperor, praying him to put himself at their head and lead them against “Perfidious Albion.” It was not certain whether the Emperor would be able to resist the pressure thus put upon him, and the ugly fact of a possible invasion of our coasts stared us in the face. It was felt that our army – most of which was abroad – was inadequate to cope with the large forces which were at the disposal of France, if they should once gain a footing on our shores, and excitement little short of panic ensued.

The people of England demanded arms that they might at least make a stubborn resistance, and the volunteer force of Great Britain sprang into life.

In its infancy its constitution was hardly worthy to be called “organisation.” A large number of enthusiastic civilians of all classes enrolled themselves under officers who, for the most part, had little or no military training, and drilled and equipped themselves in isolated companies. All worked with an energy which only determination, coupled with a grave sense of danger, could inspire. Drill went on in every town in England and Scotland; rifle butts were hastily erected, and the first rudiments of shooting were taught by sergeant-instructors from the regular army. But in spite of all this activity the volunteer army was a mere “crowd of men with muskets,” without transport, without battalion formation, and with only one suit of clothes apiece; and with such a force the only rôle assigned to them was to rush to meet the enemy, to line the hedges and walls in inclosed country; to worry and annoy the invaders in every possible way, and to die fighting to the last in order that the regular army and the militia might gain time to assemble and make their dispositions for defense, The action of the French franc-tireurs in the Franco-Prussian War shows how much may be done by such means. While matters were in this state, the scare which had created the volunteer force came to an end as suddenly as it had arisen. Napoleon III, loyal to his alliance with England, succeeded in quieting his excitable colonels, and the danger of immediate invasion was averted.

The sons of Sergeant William Cuffing of the Leicestershire Yeomanry Cavalry.

Both were from farming stock and served in Captain Story’s ‘C’ Troop, c.1860.

The volunteers now entered upon the most critical period of their whole history. The officers of the regular army looked upon them as almost useless, and either gave them good-natured but half-hearted support, or advocated their being disbanded altogether; for the British officers of that day believed only in long-service troops, drilled with all the precision of machines; controlled when in barracks with an iron discipline, and perfect in parade movements. The country would not hear of conscription; the army would not hear of short service. So for years nothing was done to reorganize the army, and the volunteers were left to live and die in an atmosphere of neglect or ridicule.

A slight advance was made by the scattered companies being formed into provisional battalions for purpose of drill, and being given a retired officer or militia officer as adjutant; and as they marched through the streets headed by the band, a crowd of street urchins ran beside them shouting such ribald cries as “Who shot the dog?” “How are yer poor feet?” and (to the mounted officers), “How much an hour for yer horse, gov’nor?” And when the battalion had reached its drill ground and deployed into line, the gamins formed line opposite to them, waiting, like the French line at Fontenoy, for the English to fire first. Then, as the rattle of the locks proclaimed the volley which terminated the “platoon” exercise, they fell down with shrieks and groans, and writhed in simulated agony of death on the battlefield, while the lookers on shouted with laughter at the performance.

When the parade was dismissed each individual volunteer went home in a storm of chaff, and the clever pencil of John Leech made fun of them in “Punch.” How they survived this ordeal seems now a miracle; but survive it they did, and set to work with a will to increase their efficiency.

It is obvious that an armed man – whether regular soldier or volunteer – is of little value for fighting purposes, unless he can shoot fairly well with a rifle; and the volunteers, recognizing this fact, proceeded at once to establish a shooting organisation throughout the country. The centre and head of this organization was, and is, the National Rifle Association, which held its meetings at Wimbledon until they were transferred to Bisley.

Quarter Master J. Kirk of the Leicestershire Yeomanry, 1841.

In every county or district, an association was formed under “Wimbledon Rules,” which held its meetings once a year, and battalion and company meetings also offered a chance of winning prizes to those who were not sufficiently expert in the use of the rifle to compete at Wimbledon. Thus an inducement was given to every volunteer to practice rifle shooting, in addition to the class firing ordered by the volunteer regulations.

The artillery have an association of their own called the National Artillery Association, which is quite separate from the National Rifle Association, and holds its meetings at Shoeburyness. It works on strictly military lines, and forms a camp where the mounting and dismounting of heavy guns, etc., as well as target practice, is a part of the regular training.

This, briefly, is the organization which, with some alterations and improvements, has continued to the present day.

The first meeting at Wimbledon opened on July 2, 1860, when Queen Victoria fired the first shot, with a rifle fixed in a rest and laid by the most experienced rifle-shot of the day, and the “bull’s-eye” flag went up amidst the cheers of a large crowd of spectators. To promote shooting at moving objects, a life-sized stag made of iron was mounted on a small railway, and ran down an incline on one side of the range, and nearly to the top of the incline on the other side, on the principle of a switchback railway, the shot having to be fired between two white posts, thirty yards apart. Sir Edwin Landseer, the celebrated animal painter, drew the stag life-size, and this splendid sketch and the “Queen’s” target are preserved by the National Rifle Association as their two most valued treasures.

In the year 1883 a team of the American National Guard came over to England to shoot against an English volunteer team. At the beginning of the match, the visitors gained a considerable lead; but at the long ranges the English team not only wiped out their loss, but succeeded in securing a hard-fought victory. In the evening both teams dined with the president of the National Rifle Association, on which occasion there were present Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Teck, the Duke of Teck, and the Hon. J. R. Lowell; the Minister of the United States in England. After dinner the rule of the association that no speeches are to be made was so far relaxed as to allow of the health of the American team being proposed by the president; and Mr. Lowell, in returning thanks for his countrymen, made one of those short and happy speeches which did so much to promote a cordial feeling between the two nations. He said on this occasion: “May God grant that in all rifle competitions between the two nations, all the rifles may always be pointed the same way” – a sentiment cordially echoed at the present day on both sides of the Atlantic.

Englishmen noted with interest during the late war of the United States with Spain, the readiness with which volunteers came forward in large numbers and at very short notice to serve their country. English volunteers in particular observed with admiration their cheerful endurance of thirst, hunger and privations of all sorts, in occasional circumstances of peculiar hardship.

That they should show courage in the field was taken for granted; but that with such short training, and in spite of hasty and, in certain cases, inadequate equipment, these citizen soldiers should develop such splendid qualities of discipline, self-restraint and self-reliance was the subject of much and hearty praise among English military critics.

The system pursued by the National Rifle Association has worked well, and although it is described as “pot-hunting” by those who wish to decry it, it has produced many first-rate shots, and may fairly claim to have carried out the object for which it was formed.

It would be impossible in the limited space of a magazine article, and would be tedious to the general reader, to treat in detail of the improvements in organization which have been carried out, from time to time, in the volunteer force; but a few words on the present state of the force may not be out of place.

The battalions are now united into brigades, commanded by brigadiers who have most of them served in the regular army, assisted by brigade majors, who are all retired officers, and a sufficient staff. These brigades assemble yearly in camp, and when at Aldershot or any other military centre come under military law, and take part in field days with the regular troops. The men learn all the duties of camp life; to pitch and strike tents, to cook and to make themselves at home in camp. A hearty and cheerful spirit animates all ranks, and the men look upon the annual training in camp in the light of a holiday, and are cheerfully prepared to perform readily all the various duties in return for the change of scene and work, and amusement and relaxation after the parades are over for the day.

As to their fighting qualities, it can only be said that they have never been tested, but there is no reason to believe that they would fight with less pluck and determination than any other men of the Anglo-Saxon race. In case of emergency, they would fight in their own country for all they hold most dear, and history has proved over and over again that men fighting under these circumstances are not to be despised, even by the best-disciplined and most highly trained troops. As regards “discipline,” that word which may mean so much or so little, it must be remembered that the average volunteer lives a disciplined life. He is not a raw boy taken from the ploughshare, nor is he a young man of fast habits who has got into some minor scrape; but he is a respectable tradesman or superior mechanic, who has a character to lose, and I have myself seen a man, when brought up for judgement in camp, tremble and turn pale at the thought of being dismissed from the service, or sent out of camp in disgrace, which, when not camped with regular troops, is the only punishment the commanding officer has power to inflict.

Such a man returns to his native town or village with a mark against him. He gets “chaffed” by the men, and – what is more important – is despised by the women. It is known that he has failed to acquit himself with credit in a duty which he has voluntarily undertaken to perform, and he has to bear the consequences.

From want of experience a volunteer sentry will, from time to time, present arms to a showy uniform, and a smart non-commissioned officer of cavalry in full uniform will receive greater honor than a general in a blue coat; but this comes from want of knowledge of details, and not from want of discipline.

A simple and practical form of drill has been introduced, which is far better suited to the volunteers than the slow, antiquated drill of thirty years ago. It is easily and rapidly acquired, and thus time is available for the teaching of outpost duty, advance and rear guards, and many other details of which in their infancy the volunteers were profoundly ignorant. The officers of the new school now at the head of the army, who no longer cling to old traditions because they were good enough in their youth, recognize that modern weapons have altered the conditions of warfare, and have long ago discarded the drill of the time of the Duke of Wellington, who for many years opposed the introduction of the percussion musket because he said “the men would fire away their ammunition too quickly.” The volunteers are now recognized as an integral part of the defenses of the country, and in consequence panic from fear of invasion is now unknown. The necessity for conscription, which is hateful to the country, and now only exists in a very mild and modified form in the militia ballot act, which is never carried out, has been averted, and it is therefore fair to claim that the volunteers carry out in an adequate measure the purpose for which they were raised, and England sleeps the sounder for the knowledge that the manhood of the population is armed for her defense.

There is, however, another important advantage which has been gained for the country. In old days the average villager had no idea of the duties of a soldier, whose occupation was described as “being shot at for a shilling a day,” and a story is told of a mother parting from her son, who had enlisted, saying to the recruiting sergeant: “How many hours a day will the poor lad have to fight, Mr. Soldier?” The idea existed that the soldier’s time was divided between fighting and debauchery, and the enlistment of a son was looked upon as a family disgrace. Many villagers never saw troops under arms in their whole lives, and the soldier and civilian were as much separated as if they were different races. This feeling is growing less and less yearly, and there is every hope that it will die out in the near future. This improvement is partly owing to amelioration in the condition of the soldiers, and the care shown for care shown for their welfare by the authorities in modern days; but it is also due to the fact that civilians are now able to give some attention to, and gain practical knowledge of, military affairs by means of volunteering. They wear a uniform, and are proud of it; they come into contact with regular troops in military centres, and make friends with the men and learn from them the details of military life. Tommy Atkins is delighted to make friends with the volunteer, and the volunteer takes a military pride in “chumming” with Tommy Atkins, and thus they gain a mutual respect and regard for each other. The days are long passed when the volunteers were alternately inflated by exaggerated praise or depressed by scorn and ridicule. They have taken their place as auxiliary to the regular army, anxious only to prepare themselves for the duties which would be assigned to them in case of emergency, and desiring to act up to their motto of “Defense, not defiance.”

© The British Volunteer Militia System in the 19th Century article by Harvey Withers – www.militariahub.com

Not to be reproduced without prior agreement.